Artist Bio

by John Paulus Semple

I hated school! I never had the slightest idea how to read either a clock or musical notes, two skills all my classmates had mastered. School was a constant fear for me. One day the teacher brought in a pile of paper plates . . . the kind used at picnics. She told us to decorate them with our supply of poster paints. It was the first day I ever enjoyed school. A day or two later, two of the school’s teachers were examining some of the plates and I heard one of them exclaim, “What a beautiful sense of design!” It turned out to be my plate, and I had been selected from the whole school to attend special Saturday art classes at the Boston Museum. Thus began my adventure in art. I must have been ten or eleven, and I went into the city all by myself, taking the train from Wollaston to South Station and then continuing on the subway. I admired my mother for trusting me.

The first day in class (there were only three or four of us) sat the most beautiful girl I had ever seen. She then proceeded to draw exquisite horses and color them in. I was amazed that she had so much talent. I don’t remember the day’s other events very well, except I loved the class and the amazing teacher who drew so wonderfully. Leaving the museum, I saw a small painting that was so good I couldn’t even imagine how a person could do it. Say hello to Mr. Canaletto! I was completely hooked. The trip home was a treat because we rode the old steam engines. Even the noise pleased me. I loved those trains and my trips on them. My love of trains is reflected in my paintings and especially in my etchings, which have often featured train yards. Well. That was my day. I had been selected from all of my fellow students on a scholarship to the magnificent Boston Museum. And for the first time, instead of failing everything, I was a success.

• • • • •

I was born in 1930 to Mildred Paulus and William Oliver Semple, of Pennsylvania Dutch and Scottish heritage, and my parents hailed from Nazareth and Easton, Pennsylvania. My father’s work as a traveling salesman for paper companies during the Depression soon took us to Wollaston, Massachusetts, where I grew up. Wollaston was a lovely New England town on the coast south of Boston.

While there were no artists in the family, my mother was a trained and talented violinist who had been instructed by her father, a musician, composer and clarinetist. But my grandfather’s early death in an automobile accident meant I was never to meet him. My loss! To this day I am touched when I hear the second movement of Mozart’s clarinet concerto.

My twin brother died at birth, but my older brother is a very talented draftsman who graduated from MIT and became a civil engineer. There was always a vein of artistic talent to be mined in my family.

After middle school I spent the ninth grade at Thayer Academy in Braintree, Massachusetts, where I did not turn my lackluster academic career around. I was then sent to Mount Hermon in western Massachusetts for the duration of my high school years. At Mount Hermon, even though I was required to repeat the ninth grade, I discovered that if I studied, I could prosper. After high school, I spent a year at Lafayette College in my native state of Pennsylvania, but by that time I knew in my heart that I wanted to paint, and they had no program. I transferred to Hamilton College. It was like coming home. I majored in art and art history and received wonderful training from James Penney and Paul Parker. James Penney gave actual demonstrations; he was the only teacher I ever had who did that. When later I started to earn my living as a painter, it was his instruction that allowed me to succeed.

After Hamilton I served two years in the Army stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey. The Korean Armistice was in place, so I spent most of my time painting signs, a skill I later took advantage of when I was jobless. I taught basic swimming to recruits, and I also swam competitively on the First Army Swim Team. I was the freestyler on a medley team that broke all the established records at Fort Dix. We practiced in an ice-cold New Jersey State Police pool, but at least I wasn’t in Korea. I frequently used to sneak away unauthorized to the Fleisher Art Memorial in Philadelphia, where I received free instruction in drawing. One day I was caught on one of my AWOL adventures, and the captain gave me a choice: take my name off the list for corporal or submit to a court martial. I chose to take my name off the list, but I would have loved making corporal. I think my punishment would have been much worse had he not liked the idea I was receiving art training.

In the 1950s, becoming a representational artist was bucking the current trend. The rage was Abstract Expressionism, centered in the New York art world, and most young artists were under its spell. This really dawned on me when I went to Mexico City College on the GI Bill in the winter of 1956. The attitudes of most of the students had been shaped by the vogue of nonobjective art. They scorned the great Mexican mural painters such as Orozco and Rivera. In their eyes, realism was on the decline, and non-representational art was the future. Thus began one of the great challenges of my career, to hone my skills as a representational artist and to achieve an acceptable level of success during a period when representational art has been in disfavor.

When I returned from Mexico, I spent the summer at the Putney Summer Work Camp. I fell in love with Vermont, and for years afterwards dreamed of moving here, though it was not to be possible for more than a decade. I also met Jerry Pfohl, who was to teach at Putney that winter. He was a tremendously talented artist who shared my passion for the representational tradition.

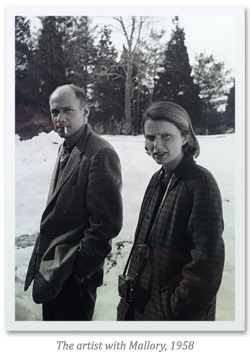

After Putney, I enrolled at Boston University on full scholarship to work on my MFA. At BU, I’m sure that I wasn’t the only art student who noticed Mallory Messner, the attractive secretary to the head of the Art Department. Mallory and I were married in September 1957. Professionally, the great benefit of BU came from my instruction in drawing from Jack Kramer, an excellent draftsman himself, but without a doubt the most important event at BU was meeting my wife of fifty-three years. Mallory has been an astute critic and constant source of encouragement. I never would have succeeded without her support.

Just before I was to receive my MFA in 1958, one of my professors arranged a job interview at a state university, where the art faculty had fully embraced the Abstract Expressionist movement. The faculty members who interviewed me pretty much told me I was out of style. One of the interviewers stressed that the mission of the program was to teach students the creative spirit, which would be killed by traditional emphasis on drawing and painting. After that interview, it was clear that my preference for representational art was going to be a real obstacle in the academic art world of the 1950s. As an alternative to academia, I decided to try for a Tiffany Foundation Grant. I submitted my application and Mallory and I took three paintings to New York. After the jury deliberated three days, we were notified we could come retrieve the paintings. When I picked up my paintings, I noticed they were the last ones stacked against the wall. I wondered: could the jury have lingered over them, debating whether they were worthy of the prize? However, I said nothing to Mallory. A couple of weeks later I received a letter that I had won (with Ben Kamahira) the top prize. And since the jury disliked the sculpture submissions so intensely in 1958, we were given the sculpture monies too. It was the largest grant ever given by the Tiffany Foundation up to that time.

I had intended to use the Tiffany money to attend the Ruskin School of Drawing in Oxford, but there was no available housing, so we headed for Florence instead. The Tiffany Grant supported us for eight months and enabled me to spend many hours in the Uffizi Gallery and the Pitti Palace, two treasures of the art world, as well as to travel through much of Italy. So much of what I have learned in painting has been through study of the great masters of the past. I have always admired the artistic values of the Renaissance in particular, and there is no better place to study its works than in Florence.

After the thrill of winning the Tiffany and the excitement of our travels in Italy, it was not easy to return home jobless. It was a low point of my career. I painted signs and worked part-time in a junior high school in Kingston, Massachusetts. (I couldn’t work full time because I didn’t qualify as an art teacher without state certification.) After four years I landed a job at my former school, Thayer Academy, a wonderful place to work. I was a successful and highly appreciated member of the Thayer faculty, and I genuinely enjoyed my time there. But ever since I had worked at Putney, it had been my dream to live in Vermont. So in 1969, I left Massachusetts and moved with Mallory and three small children to become the art teacher at the Woodstock Country School. I stayed only one year, as I was beginning to realize that it’s almost impossible to teach and paint at the same time. As she always has, Mallory encouraged me to stay true to myself in spite of the professional risks. If I’d known how hard it was going to be to earn my living as a full-time artist, I might have thought longer and harder about the decision. We had moved into an old farmhouse and were raising three young boys. I needed to sell paintings to meet the mortgage, and feed and clothe a family, which puts a unique kind of pressure on an artist. Our Vermont house, in spite of its charm, needed many renovations; much of the time I was not painting I was engaged in myriad carpentry projects. Fortunately, local and regional galleries were receptive to my work, and I quickly began to sell paintings. Now in my forties, I was a full-time artist, living in Vermont, with five galleries handling my work, and my artistic life began to change. There is a side benefit from making your living as an artist: you actually keep improving while you are getting paid to improve. I held twelve one-man shows, all successful. On the other hand, the life of a working artist does have its constraints. In those early years, I was wisely counseled to focus on figure and landscape paintings. At that time there were very few still lifes in my portfolio. Still lifes don’t always sell as well as Vermont scenery, but they are my strongest talent. I was determined someday to break out from this pattern.

One of my heroes as a young artist had been Ivan Albright, a fixture of the Chicago art world. He had made his mark in the first half of the 20th century, along with great representational artists such as Ben Shahn, Edward Hopper, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Ivan had a unique vision and style. He made many great paintings, though he is best known as the artist who painted the Picture of Dorian Gray for the film of the same name. By a remarkable coincidence, Ivan had moved to Woodstock, Vermont, only a few miles from us. Out of the blue, he telephoned to ask some questions about etching, a medium he had begun to experiment with late in his career. I was to become printer for all of his etchings. We became very good friends over the last years of his life. I learned more from him about painting than I ever had in any art school, and I will always consider him my mentor. He taught me the importance of concentrating for long periods on one painting until you “got it right and had something you were proud of.” The fact that Ivan, whom I had long admired so much, regarded me as an equal and respected my work was a huge encouragement to me in the middle of my career. It was during the same period that I began to garner more professional recognition. My work in etching was acknowledged by my election to membership in SAGA, the Society of American Graphic Artists. I began to submit my work to national and international juried competitions, and was pleased at the number of prizes I received. I began to focus more on still lifes even though I realize that landscapes are the bread and butter of a Vermont artist. Museums – here and there – have begun to add my works to their collections. In the latter part of my career, with many of the worries of supporting a family behind me, it has been gratifying to find new directions in my work. The beauty of drawing and painting is that you never achieve perfection, and you improve for your entire life.

I have always ignored the latest fads in painting; too often the motives behind them are commercial, not artistic. Ignoring them, however, imposes a penalty – you may be left out of many aspects of art, from plum teaching posts to some museums. The road to recognition has been longer and slower for me in the contemporary art environment. Fortunately, the general public has a more enduring faith in and appreciation for the representational tradition. Late in life, the pendulum of artistic values is beginning to swing my way. You must learn how to paint and draw; art should deal with both personal visions and objects that interest and delight the eye. I have felt honored to be one of the last artists to work in the Renaissance tradition of drawing and painting and observing from nature.